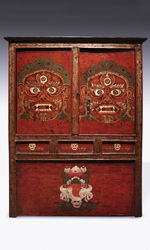

Tibetan Monastery Cabinet Depicting Mahakala

|

|

"It can be said with certainty this cabinet was used in a monastery because of the depiction of the deity Mahakala on the two door faces. Mahakala is considered a particularly important deity in Buddhist practice and is perhaps the most important of the Dharmapala, the guardians of the laws of Buddhism"

Only recently has it become possible to discover the full range of Tibetan furniture, since little emerged until the 1980s, when this type of material first began to appear on the international art market. Up until that point, the furniture remained where it was used, primarily in monasteries and a scant amount in homes. However, during the Cultural Revolution in China all this changed. Most of Tibet’s monasteries were destroyed and the furniture that was found there and in homes was either carted over the Himalayas by those fleeing the country, finding its way to India; or was sold to the Chinese by others who used this money to escape.

|

|

Regardless of how this furniture first began to appear on the market, there does not seem to ever have been much furniture in Tibet to begin with, primarily because the population of Tibet has always been small and traditional ways of life for ordinary people did not require any significant amount of furniture. Even the aristocracy, composed of government officials, religious leaders, and their families used a limited number of furniture types compared to other cultures. For example, no tradition developed of making seating or beds because the vast majority of Tibetans preferred to sit and sleep either on the ground or low, cushioned wooden platforms. Household goods were commonly hung from the walls, and those used less frequently were stored in woolen sacks or yak skin bags. Only precious goods such as finery and jewelry might be deposited in a special chest, and this chest would be found in the religious rooms of the monasteries, houses or tents where Tibetans typically lived.

Consequently, there are a limited number of Tibetan furniture types. Essentially, the vast majority of Tibetan furniture falls into three basic categories: trunks and boxes (essentially a box accessible through a lid), cabinets (boxes accessible through doors), and tables. A fourth type of furniture – shrines or altars – might be considered in a broader discussion of this furniture; however, tables were commonly used as altars upon which was placed offerings such as fruit, incense, butter lamps and if available, statuary.

|

|

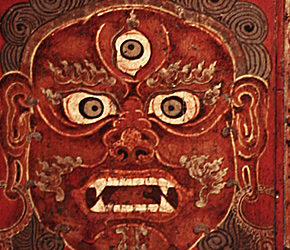

It can be said with certainty this cabinet was used in a monastery because of the depiction of the deity Mahakala on the two door faces. Mahakala is considered a particularly important deity in Buddhist practice and is perhaps the most important of the Dharmapala, the guardians of the laws of Buddhism. In a discussion of this cabinet, it is important to remember that although the monasteries were the social, political, economic, and religious hub of Tibetan life and places were many activities occurred, they remained the center of Buddhist worship.

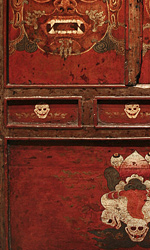

Almost all Tibetan furniture was painted as this helped hide the simple joinery of the furniture and Tibetan taste preferred vivid painting to the subtlety of wood grain. The virtual absence in Tibet of high humidity and insect pests, the two main agents of the destruction of wood, as well as the protective coating of butter-lamp soot and the comparative safety of the monasteries allowed for the preservation of pieces which now have considerable age. This piece, for example, is estimated to be well in excess of 200 years old. It is part of a particular class of cabinets called torgam, which in essence, are shrines, or altars typically used to house ceremonial sculptures, especially those fashioned from butter and barley meal called torma. If the torma depicted fierce guardian deities, then the torkam was fashioned with doors and the statues were concealed. That is the case with this cabinet. The torgam was kept in a special shrine room called a gokhang found in the monastery. The torgam is possibly the first type of furniture to be developed to address a specific requirement of Tibetan Buddhist ritual and practice. It is extremely difficult to find authentic examples today.

Finally, in regard to the painting, it can be said that Tibetan taste favored certain motifs and formats that were derived from early Buddhist decorative arts traditions as opposed to arts traditions from surrounding cultures. Sometimes, strictly religious motifs were tempered by embellishment, alteration or abstraction to perform a more decorative function so the piece might be considered more pleasing to the eye. This is not the case with this piece, as the imagery conforms to traditional Buddhist practice and what might be called traditional Tibetan motifs and “canons of depiction.”

As noted before, this torgam features two faces of Mahakala on the door fronts. Mahakala is considered the “defender of the law,” a reference to his role as the protector of the dharma, or teachings of Buddhism. His appearance on the cabinet is a direct indicator of the piece’s purpose. Also of note is the painting on the lower face plate of the cabinet. It depicts a traditional Tibetan motif called Wangpo Nagna, which translates as “five senses.” This motif is composed of stylized body parts; specifically, the eyes, ears, nose, tongue, and heart. This is a direct reference to sight, hearing, smell, taste, and our emotions, the five senses that can keep an individual from achieving a complete state of liberation or enlightenment. On the three small face panels above the bottom plate are depictions of skulls. In Tibetan Buddhism the skull is a symbol of impermanence.

|

|

Download this Article: Tibetan Monastery Cabinet Depicting Mahakala.pdf