A New Spin on an Old Debate – Collectible Globes

PRIMITIVE - Friday, March 03, 2017 |

|

By Misaki Imagawa & Glen Joffe

Editor’s Note: Originally written in 2014, what follows is an updated version of our blog dealing with Collectible Globes, which by abstention could be extended to maps. It has been expanded to give a bit more background information on globes in general and to cover the topic of celestial globes as well. As humankind reaches for the stars, these instruments reveal more and more of our knowledge about the heavens and what lay beyond our earthbound borders. The allure of both terrestrial and celestial globes as a collecting category has increased over recent years as more and more people have been exposed to the art form and become intrigued by the worlds they delineate. The transcript below is from a fictional conference held at PRIMITIVE to determine who discovered America. It remains the same.

Welcome attendees. Today we are holding a conference to debate a topic of much contention: Who discovered America?

“I did, of course,” said Columbus. “October 12, 1492. There’s even a federal holiday in my honor.”

“Well technically,” said Zuan Chabotto, also known as John Cabot in England, “you landed on Cuba and Hispaniola, not mainland America. I landed in America a full year before you did.”

“And he set sail from England,” yelled an Englishman from the audience. “He even received funds from King Henry VII.”

|

|

“Ah, excuse me,” interrupted another audience member, this time an Italian. “Henry only gave him a fraction of what he needed. Chabotto’s main investor was an Italian banking house in London. We financed the voyage.”

“Wait a minute,” said Englishman, John Day. “I wrote a letter to Columbus in 1498 saying that the land Cabot ‘discovered’ had already been discovered by English seamen as early as 1470.”

A moment of silence descended on the room. Then the Viking Leif Erikson from Greenland spoke up. “I was long gone by 1470. It was around the year 1000 that I took 35 of my men and set sail to the west.”

Bjarni Herjolfsson, the Icelandic trader said, “I told Erikson about the time I was blown off course some ten years before that and saw this mysterious land to the west of Greenland.”

“We landed and spent a winter in Vinland,” Erikson said. “I believe it is now called Newfoundland.”

“Yes, but we discovered the American continents 40,000 years ago,” said a weathered Chinese sailor, quickly joining the debate. “We drew a map to prove it,” pulling a scroll from his coat.

“That’s unsubstantiated!” declared Chabotto. “There’s no way you can prove its authenticity. Here’s a copy of a European map created in the 17th century. It proves I was the first to set sail to America with the intention of finding America.”

“It’s still Columbus Day, not Chabotto Day,” declared Columbus.

“Argue all you want,” said a Native American addressing the entire assembly. “We were here first.”

|

|

|

The topic of who discovered what and when has long been debated by historians whom may never come to a singular agreement. One thing is certain: humans have continually dreamt of faraway lands and set sail to voyage to the edges of the earth and beyond. As with all things in human history, people have left records of their voyages and discoveries. From the earliest maps that were mere lines and dots on a cave wall to increasingly detailed and accurate world maps and globes, the field of cartography reflects humankind’s political and geographic history. You might also say these types of “documents” illustrate humankind’s desires, ambition, struggle for community, and even, folly.

|

|

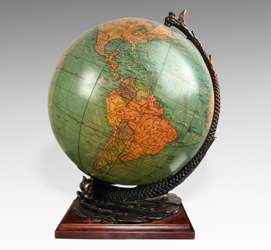

In the 2nd century BC, roughly a century after the notion of a spherical Earth was accepted in Greece, Crates of Mallus created the earliest known terrestrial globe. You can imagine the staggering transformations globes underwent as new continents and countries were discovered over the centuries. Each time a new discovery was made or a change took place – for example, one country or empire was replaced by another - globes previously created became windows into the past, spherical snapshots in time and therefore highly collectible. However, it isn’t just world changes that make the many globes in PRIMITIVE’s collection worth owning; it is also their artful craft and design.

|

|

In essence, there are two types of globes: terrestrial and celestial. Terrestrial globes present a spherical model of the earth. Those produced by renowned globe makers do their best to present the earth without distortion. They illustrate continents, political borders, changing land masses and their features, and even our increased understanding of underwater topography as well as air and water currents. At one time, globes were used by politicians, seafarers, and even the military as useful planning tools. They were also used by educational institutions and libraries as a means of exploring and discovering various aspects of the earth. However, today globes are universally created for educational purposes only as they have been rendered “technologically obsolete” due to the advent of more accurate high tech mapping, tracking and recording devices such as GPS. Yet, the fact remains that globes still present historical documents reflecting political and topographical changes in the earth as history moves forward. The moment a change occurs the last globe made becomes – at least partially – obsolete, and in many instances more collectible as a result.

|

|

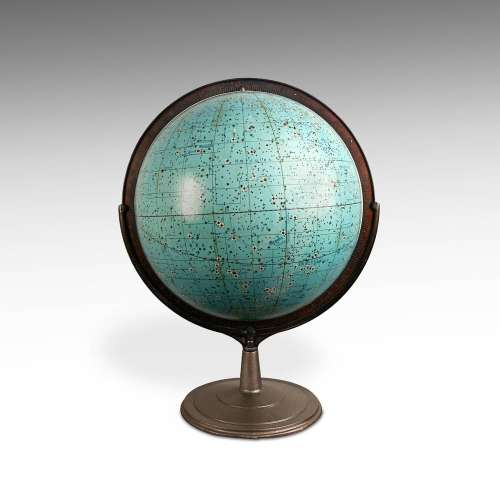

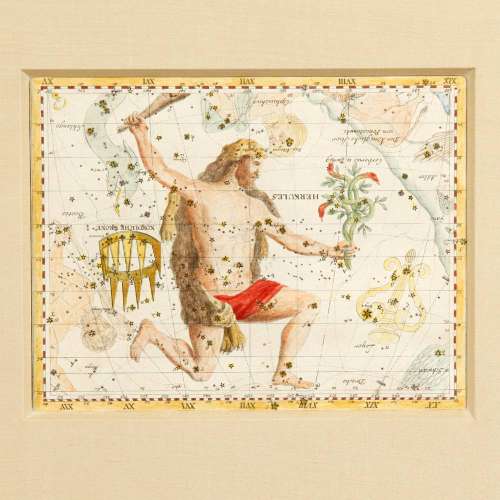

The second type of globe is the celestial globe, which shows the positions of the stars in the sky. Typically, they do not show the position of the sun, moon or planets because these bodies vary in position relative to the stars. Generally speaking, celestial globes are more difficult to use than their terrestrial counterparts. This is because the view from the earth is positioned at the center of the celestial sphere whereas the globe is viewed from the outside. For example, a celestial map will depict a constellation as it appears to the viewer on earth, but a celestial globe will show the mirror image of the same constellation if it is faithful to the viewer's orientation, which, in effect, is out in space. Consequently, celestial globes are frequently produced in "mirror image" relative to the observer’s viewpoint. This way, the constellations will appear correct relative to how they appear on earth. Celestial globes not taking this into account must be viewed in a mirror for constellations to have their familiar appearance, and these types of globes often have the names of heavenly bodies printed in reverse as well.

|

|

Part of the allure of all globes - terrestrial or celestial - is they make the world look smaller and the known universe more accessible. It doesn’t take hours on a plane or days in a car to cross the United States – it’s simply the slide of a finger across a rounded map. You can engage in warp drive the moment you turn a celestial globe. Going from Europe to Asia is just a small spin on a terrestrial globe’s axis. Visiting Alpha Centauri is equally easy with a celestial globe. Suddenly, friends and family living on the other side of the world don’t seem so far away with a terrestrial globe; and with a celestial globe even the vastness of the Universe may not seem so daunting.

Pick a place on the map and put yourself in the shoes of Columbus, Chabotto or Erikson. Become an officer on a starship and look out at the universe with your naked eyes. If you're earthbound, can you see Cuba, Newfoundland, the new world? If you're out in the universe can you spot any familiar points of light? Become a voyager who sought fame, fortune and adventure mapping the world; or perhaps an explorer from the future looking for new worlds entirely. Smell the ocean, see the wind billowing the ship’s sails, listen to the creaking and groaning of the ship as it cuts through the waves and rides the swells. See the stars shoot by as you approach light speed. Past, present or future - ahead lay undiscovered worlds. Your hands are not just touching a spherical map. They are connecting you to the accumulated experiences of every pioneer who has gone before, is living or hasn't been born yet; every single person who has or will open their eyes and decide to take the world in their own hands.