Fascination with Death – Skull Symbolism

PRIMITIVE - Friday, October 21, 2016Edited by Glen Joffe

|

|

What happens when we draw our final breath? Nobody really knows, except perhaps the dead. Death has fascinated the living for thousands of years. Burials, one of humankind’s earliest rituals, provide evidence of reverence for the dead and whatever lay beyond. Some cultures believe in heaven and hell. Others believe in reincarnation. Whatever any particular culture believes about death and what happens afterward, religious teachings and imagination play a central role in those beliefs. Yet, there is only one hard fact illustrating what remains after death: bare bones; especially, a grinning skull.

|

|

Throughout history, the skull held special significance in religion, art and the world of decorative design. However, its symbolic meaning varies greatly between cultures and religions, and what any individual perceives is often tempered by personal aesthetics and fashion. Traditionally, the skull represents death, evil, fear and mortality; but it can also symbolize the complete opposite: protection, power and gratitude toward life. Regardless of its symbolism, the skull stands as a constant reminder that no one can escape death. For example, the appearance of skulls on some Christian rosaries is said to reflect the Latin expression Memento Mori, meaning ‘remember that you shall die.’ Rosaries of this sort thus serve as a reminder to live life with the knowledge of judgement after death. The skull motif is also closely tied with Jesus who was crucified on the hill of Golgotha, translated as ‘the place of skulls.’ Though it may have been a reference to executions that took place on the hill, a great deal of Christian art from later centuries featured skulls at the base of Christ’s crucifix to symbolize his resurrection and victory over death.

|

|

|

In stark contrast to the appearance of skulls in Christianity, Tibetan Buddhism viewed the skull very differently. In the Himalayas and in some regions of Central Asia, an ancient form of burial was practiced, known in the West as a “Sky Burial.” In Tibet, it is called Jhator, meaning ‘Alms for the Birds,’ a tradition that is still practiced in some areas today. Bodies of the dead are ceremoniously prepared and then left on a mountaintop for scavengers or carrion birds to consume or to naturally decompose. In this area of the world, the harsh climate, rocky landscape, and scarcity of fuel made it difficult to dig graves or cremate bodies. Sky Burials had considerable religious significance, symbolizing the soul’s ascent into a new life cycle through reincarnation.

|

|

In some Sky Burial’s, the skulls of the dead were retrieved. Believed to be karmic vessels holding spiritual powers, the craniums were then elaborately carved with decorative motifs and adorned with jewels and silver ornamentation. These were called Kapala and used ritually to hold dough or wine, representing sacrificial offerings of flesh and blood to wrathful deities. Mahakala, one such frightful deity, is always portrayed with a crown of five skulls and often holds a Kapala in his left hand. Though Kapalas made of real human skulls are now rare, their symbolic significance lives on and extends further as a distinguished art form.

|

|

In western art, the skull motif rose to prominence during the Medieval and Renaissance periods, becoming a central theme in Vanitas paintings. The Latin term Vanitas means ‘emptiness,’ and was used to indicate the futility of earthly pleasures and pursuits. The word was later translated to English as ‘vanity.’ Closely related to objects conveying Memento Mori ,Vanitas paintings expressed the fleeting nature of life and pleasure as well as the inescapable certainty of death. Beautiful flowers, ripe fruits, objects of value and attractive female figures were depicted alongside bare skulls to convey the idea that flowers wilt, fruits rots and no amount of beauty or wealth can save you from death.

|

|

In the following centuries, the skull continued to fascinate European artists as a symbol of death and mortality. Yet, beyond symbolism, the aesthetics of the skull’s form also fascinated these artists. Paul Cézanne painted a series of skulls in his later years. Pablo Picasso was another artist who was allured by the symbolism and visual beauty of skulls. Like Cezanne, he kept a number of them in his studio and many of his works reflect both a careful study of the form while evoking an atmosphere reminiscent of the Vanitas style.

|

|

|

|

|

||

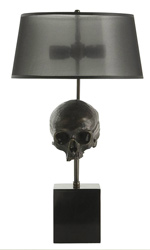

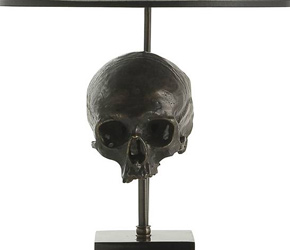

In the second half of the 20th century the skull entered the world of design and fashion. The use of skulls in propaganda art during WWII may have helped pave the way for artists to adopt the motif into the mainstream world of decorative design and pop art. Today, the symbolic significance of the skull is recognized as it has been for hundreds of years, and this rich history may account for its widespread popularity among contemporary collectors and consumers alike. The skull has found its way into decorative accents, furniture designs, jewelry pieces, fashion accessories and fine art. It continues to elicit fascination, unease, attraction and repulsion, for as much as it represents death and finality, the fascination with the skull continues to endure and endear.

|