Painting the Mysteries of the Great Unknown – Jain Artworks

PRIMITIVE - Friday, August 15, 2014 |

|

Northerly Island |

By Misaki Imagawa

Someone once told me that one of the most impressive views of the city in Chicago is on the far corner of Northerly Island – and they were right. Past Millennium Park, beyond Buckingham fountain, and near the museum campus is one of the most beautiful views I’ve seen of Chicago. When you’re in the city everything is tall, cramped, noisy and bustling. Getting a chance to take a step back and see things in a different scale really puts things in a unique perspective. You even notice things that seem so obvious in hindsight – like the stars, for instance. I had already been living in Chicago for a year, yet I noticed the stars for the first time when I was on Northerly Island. It is no coincidence that the Adler Planetarium is positioned there, separated far from the downtown lights, peering up at the night sky above Lake Michigan. Though I know very little about constellations, the myriad of bright stars sprawled across the sky never fails to fascinate me.

|

|

Carl Sagan once said, “Astronomy is a science that seeks to explain everything.” Although the late astronomer was a popular figure in modern times, people have been looking up towards the stars for thousands of years. Jainism, for instance, is one of the oldest religions in the world, yet it does just what Sagan declared in breathtaking detail. The origins of Jainism and much of its beginnings may be obscure; however, it encompasses an unbelievably deep body of literature and doctrines. These include artistic depictions regarding history, meditation, religious practice, ethics, and cosmology. Of these, I find cosmological paintings of the universe the most stunning. According to Jainism, there is no beginning or end to the universe; it has always and will always be in existence. Jains believe everything in the universe is in constant flux – nothing is ever destroyed and nothing is ever created. Instead, all living souls and non-living entities change forms over time from one to another.

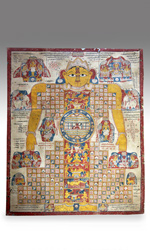

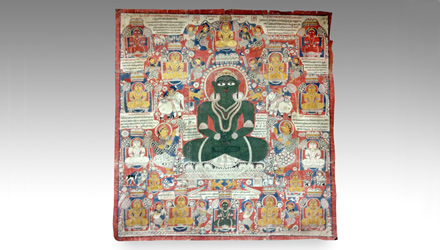

Visual depictions of Jain cosmology are intricate and highly compelling. The texts illustrate the universe as being shaped like a man, broad at the top, narrow in the middle and broad again at the bottom. Consequently, images called Lokapurusha, or images of Cosmic Man depict several different worlds for the liberated, celestial and mortal beings, as well as a multi-tiered hell. In Jain painting, the universe is also depicted as a cosmic wheel of time, of which our individual lives are but pin pricks. These types of paintings are called Manusyaloka, or Maps of the Human World. Another type of cosmological painting illustrates historical figures and their attributes. For example, a depiction of Jina Parshva, the earliest Jain leader for whom there is historical evidence, is meant to illustrate compassion.

|

Perspective can sometimes be a frightening thing – to realize that we are all miniscule pieces in the grander scheme of the universe. Rarely do we raise our eyes to the sky in the middle of downtown Chicago, but out on Northerly Island the eye is naturally drawn to the horizon, the cityscape and beyond. While science may have uncovered some of the facts hidden up in the skies and space, there still remain many more mysteries. These same mysteries fascinated Jain scholars of old, inspiring them to seek answers to great questions about the universe and creation, thus inspiring this intricate art form. Jain artistic depictions of the cosmos came from the very same curiosities humankind has harbored for tens of thousands of years. They are most evident when we look up at the stars, out into space, and into the great unknown.

|

|

Download this Article: Painting the Mysteries of the Great Unknown.pdf