Q&A with Artist Mark Westervelt

PRIMITIVE - Friday, June 05, 2015By Misaki Imagawa

|

|

Mark Westervelt is an award-winning American painter. He received his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in painting at the Kansas City Art Institute and completed his formal studies in Chicago, where he received a Master of Fine Arts in painting at the University of Chicago.

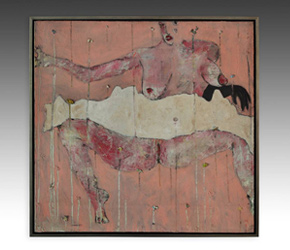

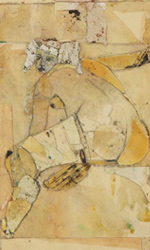

While a classically trained artist, Westervelt’s art has transformed over the course of his career to incorporate various mediums. Most notable is his ingenious use of dried paint, which creates a unique three-dimensional texture to his emotionally powerful paintings. Artists are constantly striving to create something new, but few can claim inventing their own medium; Westervelt can. His use of dried paint is unlike anything else found in contemporary art today.

|

|

Westervelt’s paintings reflect a certain raw primitivism that is both moving and seductive. His works are emotive, almost always featuring faces and figures assembled from the skins he creates and tempered by his imagination. Though at first glance his pieces may seem abstract, the facial expression and body language of his characters convey a never ending array of feelings and conditions. They may express struggle, confusion, serenity, humor, frustration, or clarity. The list is never ending. Yet, regardless of what his works convey, they express a singular visual language reflecting a devoted artistic genius.

Editor’s Note: Below is a Q&A session with Mark Westervelt designed to shed some light on his artistic process and how his work has evolved over a long and illustrious career.

|

|

Your artworks have multiple layers of materials and textures. Could you explain what your process is like and what kind of materials you use?

MW: I work with dried paint. Many years ago I was painting on a canvas and the paint kept dripping onto the floor. So I laid out a sheet of plastic to protect the floor and when the paint dried up I was looking at it and thinking what a waste it was – I had to get that paint back onto the canvas. So I glued it onto the piece I was working on to create some texture. The randomness was beautiful. I saw faces and images in the dried paint chips and started using them as key components of my work.

|

|

Then the science of paint changed. They don’t make oil paint the way they used to; it was more toxic back in the days. In other words, it was more caustic and it dried differently than now. It was more textured. Now I use acrylic and latex paint, which has even more elasticity. I first paint on plastic and then peel it off, leaving me with a sheet of paint. I glue this onto the material I am working on, such as a 10x10 inch wooden block canvas as the base layer, and then I use other paint skins to create a face or the subject of the piece – like an appliqué. It is also like monotype printing on paint, not paper. There are two sides to each skin: the side that is directly applied to the plastic is glossy and the side that is exposed to the air is matte. This provides me with two different sheens, both of which I use in my works.

What are the difficulties and advantages of working with dried paint?

|

|

||

MW: One of the difficult things with what I’m doing now is that everything is backwards. You sometimes see text on my work, but all that has to be written backwards so that when the paint is peeled off, the letters read the right way around. Likewise, if I want a person to be looking left, I need to paint him looking right. It is like reverse glass painting in that the image is reversed when it’s peeled up. Another difficulty is that when there’s something I don’t like or want to change, I can’t just dot it out or paint over it. I need to create a new paint skin or find one with which I can appliqué another layer.

On the other hand, working with dried paint, whether it is in chip or skin form, allows me to fulfill my interest in collage, assemblage, and printing without cutting up magazines or attaching miscellaneous items to the canvas. I stay true to my original discipline of painting. I paint – just with dried paint. I also enjoy how much is left to chance. Working with dried paint and paint skins has largely to do with manipulating spontaneity, even if that is an oxymoron.

|

|

Faces and figures are constant subjects of your artwork. What keeps you returning to them?

MW: The recent portrait series at PRIMITIVE is presented in the tradition of documentation. That is to say that the presentation is straight forward: the story lies in the face. This has been a formal and standard composition for portraiture for all time. The face, head and bust are ancient and iconic in their history as well as in their presentations – atop a pedestal, wanted poster, milk carton, huge billboard, architecture, hanging high on a wall, etc. This is how I see them in reference to some of the portraiture of the past.

I’m interested in being human and using the figure allows me to best express this with my visual language. The figure is an image that all humans can relate to, providing me with the opportunity to translate my thoughts, feelings, and experiences into my work. The figure continues to inform and interest me even after 35 years.

|

|

Your works often depict people in extreme states. Where do you draw your inspiration from?

MW: I express inner conditions of the self in my works. The emotive quality that lives in my images comes from an internal investigation. If I’m confused about something or struggling with an issue, I infuse my paintings with these feelings. They’re emotive and contemplative, and they show whatever struggle or journey I’m on. Most of my works are figurative paintings, but sometimes they are of plants or animals in human form. It’s all about my personal emotions and the evolution of the self.

What about the titles?

MW: I sometimes come up with a title while I’m creating the work, then when it’s finished and has been sitting in my studio for several days I’ll change my mind and come up with a new one. Other times, I won’t have a clue what the title’s going to be until I finish. One critic actually said he didn’t want me titling pieces since he didn’t want to be told what they were about. There are two things I want people to think when they look at my work: “wow” and then “what?” I want the viewer to be seduced and then confused.

Many of your past works are small format, roughly 5x7 inches. What appealed to you about this size?

MW: Many of the paint chips were small so they made up smaller images, which led to the downscaling of size.

|

|

||

How long does it take for you to complete a piece?

MW: The process takes quite awhile – like most art processes. It takes about three days to make a skin and then it can take anywhere from a day to three or more days to complete a piece, but finishing a piece is the hardest leg of the journey. I never know when a piece is complete until it visually speaks to me. I’m guided by intuition, chance, imagination, and circumstance. I feel I can always do more to a piece to make it better. Some say you only make one painting your entire life. For me the work tells me when to move on. I am only aware of the forces that course through me and the images.

|

|

What are your plans for future projects?

MW: I’m starting to work with 3D sculptures. I take wooden armatures and paint over them. I’m also planning on working in modular components, so that I can create and assemble multiple panels to make up larger images. This will be a way for me to create works on a bigger scale.

What do you think of the contemporary art world today and how would you describe yourself?

MW: As far as what is currently happening in contemporary art today, I am always humbled at the level of talent out there. There has and always will be great artists. I am not very interested in the new high tech video audience participation type of art though. My influences are infinite. I am influenced by artists such as Picasso, Matisse, Dubuffet, De Kooning, Fischl, Salle, Gucci, Magritte, Avery, Park, Twombly, Clemente, Baselitz, and Polke; and also outsider art, primitive art, children’s art, and of course the old masters. That said, if a label must be attached, I am okay with being called a figurative abstract expressionist.

|

Download this Article: Q&A with Artist Mark Westervelt.pdf