The Art of Faith – Mexican Retablos

PRIMITIVE - Friday, June 17, 2016Edit by Glen Joffe

|

|

One of the most delicate subjects to talk about is faith – yet everywhere we go, it is present. It might even be said faith is a universal concept, even if how it is applied may differ. One person has faith in one religion, one person another religion; one person believes in one particular god, another believes something altogether different. Teachings may differ, but the idea of faith does not; and as a concept it is usually applied to religious concepts. No wonder; has there ever been a civilization that did not believe in some form of gods, deities, spirits, ancestors, priests, shamans, medicine-men, the 'other world' or any other sort of supernatural force that interceded in the realm of humans? So great has been the influence of religion on history, it seems difficult to find major historic events and wars that have not been triggered in the name of faith. From territorial expansions to explorations of new lands, missionaries spearheaded the conversion of indigenous people, oftentimes permanently changing their cultures; yet, it was not always violent and forceful. In some instances, missionaries and emissaries found common ground with indigenous religions, and this was the case in Mexico when Spanish colonists arrived.

|

|

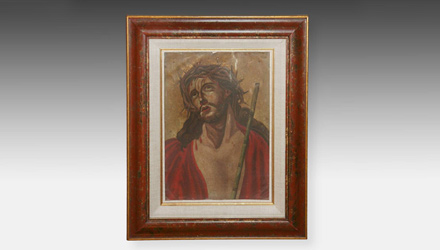

Nonetheless, the conversion in 16th century Mexico to Catholicism was not without conflict and resentment from the indigenous people as old temples were torn down and replaced with Christian churches. Even greater, however, were the striking similarities that emerged in the practice of Christianity and the native religion of the area. For example, baptism, rituals of communion and the worship of iconic images were common to both religions. Parallels could also be drawn between the indigenous gods and Catholic saints, especially the Virgin Mary. The missionaries therefore did not attempt an outright destruction of previous beliefs, but a shift of the pre-existing faith to conform to Christian doctrines. Though history texts relate all the details of the Mexican Inquisition, unique artworks called retablo more effectively capture the spirit of Mexico's adaptation of Christianity.

|

|

|

Retablo derives from the Latin term retro tabula, meaning 'behind the altar.' Altarpieces in Europe developed around the 11th century as carved and painted panels depicting figures of Christ, the Virgin Mary, the apostles and saints. By the late Middle Ages altar pieces in Spain evolved into great architectural structures, often made of carved and gilded wood rising from the floor almost to the ceilings of churches. When Spanish missionaries arrived in Mexico they brought the tradition of altar pieces with them, but instead of erecting elaborate altar pieces in churches they used smaller devotional paintings of saints to spread the teachings of Christianity and convert the indigenous people. The practice of venerating sacred objects representing various gods had already been a long-standing tradition among pre-Columbian cultures, connected with the belief that such worship would ensure good health, rainfall, abundant harvests, fertility, and protection. In a sense, having faith in indigenous gods or patron saints was still having faith, and making the transition from venerating objects to pictures of saints was not a huge leap.

|

|

Eventually, the saints depicted in retablos acquired a distinctly Mexican nuance. Stylistically, they mostly remained loyal to Christian iconography, but some acquired new names and functions as they were integrated into Mexican culture. For example, the old Aztec deity Tonantzin, meaning 'Our Mother,' was replaced by Our Lady of Guadalupe, which is widely accepted as the Virgin Mary. As Tonantzin was the goddess of rain and fertility, the same powers were endowed on the Virgin. She was also given the same feast day. In other instances changes were introduced by the clergy itself. This is how a dark-skinned Christ on the crucifix came to be. It was an effort to move the indigenous people toward identifying and sympathizing with Christ's sacrifice.

|

|

Retablos were first painted on wood and canvas for churches and later on sheets of copper. These were expensive materials, limiting the distribution of paintings only to those wealthy enough to afford them. It wasn’t until the 19th century, when cheap tin sheets became available that the retablo industry flourished and paintings of saints became affordable to every class. However, unlike paintings created on canvas and copper, those painted on tin were usually executed by artists who were self-trained. They copied figures of saints as seen on imported European paintings or from retablos painted by academically trained artists. However, as a form of folk-art tin retablos often expressed a greater sense of creativity and personal interpretation. In a twist of fate, retablos today are often viewed as fine art since the skill exhibited by the artists who painted them frequently rivaled that of their trained colleagues.

|

|

It is interesting to note that even though most extant retablos date from the mid to late 19th century, the paintings are usually executed in an earlier Baroque style. The Baroque style was the dominant art movement in the 16th and 17th centuries when Spanish missionaries first brought Christian artworks to Mexico. That the style prevailed in later centuries suggests most retablos were painted in rural areas far removed from large cities where newer artistic styles became fashionable. Nevertheless, many retablos demonstrate slight variations from the traditional Baroque, which further suggests individual unnamed, untrained artists had the freedom to exercise their own idiosyncrasies and develop their own individual styles.

Retablos are usually regarded as folk art and religious art, painted mostly by common people for consumption by other common people. Outwardly, they represent Christian art work; yet, their story is immersed in a far deeper blend of Catholic and indigenous religion as well as European and pre-Columbian cultures. As objects of veneration, retablos illustrate more than saints. They depict the power and universality of human faith. Although advancements in science may dramatically change the way we look at religion, will those views ever erode humankind’s displays of faith? If those displays of faith erode, will retablos be any less meaningful – or will they remain as potent reminders of the universal concept of faith?

|

Download this Article: The Art of Faith – Mexican Retablos.pdf