The Great Leap – Chinese Cultural Revolution Memorabilia

PRIMITIVE - Friday, February 20, 2015 |

|

By Misaki Imagawa

Depending on who you ask, life during China’s Cultural Revolution was many things: terrifying, brutal and exhausting to some; yet to others it was also moralizing, bolstering, and in several aspects even innovative and modernizing. But there was one underlying factor – or more accurately, one underlying figure – that was a part of everyone’s life: Mao Zedong. Every morning, the first thing you saw when you opened your eyes was Mao. The last thing you saw before closing your eyes at night was Mao. There was no home that did not prominently display his framed portrait or carved statue. You would bow in front of the portrait and recite memorized quotations from the ‘Little Red Book,’ formally known as the ‘Quotations from Chairman Mao.’ Before breakfast you would ask Mao’s portrait for the day’s instruction; at noon you would thank him for his kindness; at sunset you would report the day’s events. Mao was literally everywhere.

|

|

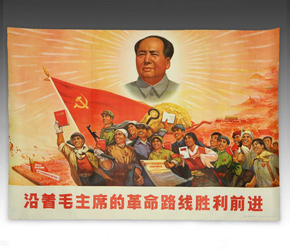

Propaganda posters featuring Mao appeared as early as the 1950s but it was during the Chinese Cultural Revolution that they reached their peak. The ‘Little Red Book’ was so named because it was small enough to be carried around in everyone’s pockets – and carry it they did. If a Red Guard demanded to see your book and you failed to produce it from your pocket the punishments could range from verbal and physical abuse to being sent to hard labor camps. Badges featuring Mao’s face were also worn by all, mostly pinned to clothing – or even through the skin above the heart in some overzealous cases. Billions of badges and pins were produced and distributed at this time. Modern scholars estimate that the amount of metal used to make the badges could have produced nearly 40,000 fighter jets. Even Mao saw this as wasteful and called a stop to badge production in 1969, purportedly saying, “Give me back my airplanes.”

|

|

However, the propaganda posters and slogans continued on, all depicting a utopian society where food was plenty, the people strong and healthy, children having unwavering faith and confidence in the state, and everyone appearing happy. Soldiers were always shown as being brave, and farmers were always smiling joyously as they worked the fields. Technological advancements always reached the people; and, of course, everyone flocked loyally and lovingly around their flawless leader - Mao, the benevolent father, wise teacher, leader of the people and politicians, and the great commander. In short, he was the Helmsman of the People.

|

|

|

The Cultural Revolution arguably ended with Mao’s death in 1976. In the years following, the Communist Party began a steady process of “de-Mao-ization.” Much of the memorabilia and propaganda posters were destroyed, statues were taken down, and badges were collected and melted down into functional objects. Yet, there could never be a total dismantling of the “cult of Mao.” The faith, worship and loyalty he had received had not been a complete fabrication. Children and youth of the 50s and 60s were raised to adore Mao, and so they did. Even today with the power of hindsight, many believe that ‘The Great Leap Forward’ – which resulted in millions starving to death, and the Cultural Revolution, destroying centuries of precious Chinese history and traditions – were nothing more than ‘mistakes’ made by the Great Leader in his old age.

|

|

Are those opinions merely the lingering effects of successful propaganda campaigns, or is there a different side to it? The answer is both. Mao was indeed responsible for the destruction of many historical artifacts and heirlooms, as well as the forceful ejection and relocation of millions of scholars and intellectuals from their educational institutes to labor camps. However, at the same time his government seized control of scientific and technological institutes, and under their rule, made significant innovations in areas such as military technology, geology, agriculture, chemistry, space science, and industry. Among their greatest achievements during the Cultural Revolution, China launched its first successful satellite, detonated its first hydrogen bomb, and completed its first nuclear submarine, propelling them into the world as a modernized nation and a power to be respected.

|

|

In his final years, Mao also did what was, until then unheard of and unprecedented: he reached out to the United States. Mao’s invitation in 1971 to a US table tennis team playing in Japan began an era known as “Ping-Pong Diplomacy” between China and the US. This culminated in President Nixon’s visit to China in 1972, and paved a foundation for the relations that continue today between the two countries. Could anyone else but Mao have done this? Would anyone else have had the unwavering support – through adoration, fear, or both – of an entire nation?

|

|

|

The propaganda art that remains today, which predominantly features Mao, prompts these very same questions. Yet, they also represent something more, something deeper than the subjects they portray. The vibrant colors of utopian posters have faded to reveal stories of turmoil, oppression and hunger that was a reality for many Chinese back then. Mao’s quotes no longer dictate the Chairman’s words. Instead, they tell the story of the people who read them. Porcelain figures of Mao represent more than the person. They reflect pivotal moments in modern Chinese history. Buttons and pins act the same way. All these works may be categorized as propaganda art; specifically, Cultural Revolution memorabilia. Yet, the history and stories embedded in each item speak of something greater. They address lives that were swept up in the Cultural Revolution. They tell stories that were left untold professing ideas that were lost and found, and ultimately, the legacy of the man who left it all – both good and bad – in his monumental wake.

|

Download this Article: The Great Leap.pdf