Art in Bloom – Japanese Jubako and Fubako

PRIMITIVE - Thursday, April 14, 2016By Misaki Imagawa

|

|

Springtime – Nara, Japan

A small cherry blossom petal landed abruptly and silently in a cup of chilled barley tea. Shinobu, the man cradling the cup found his gaze drawn to tiny ripples spreading across the surface, momentarily forgetting what his wife Chiyo, was talking about. A gust of wind blew across the hillside meadow where they sat picnicking under the Sakura trees in full bloom. Chiyo hurriedly stacked traditional lacquered food boxes filled with their lunch to avoid any petals landing inside, but Shinobu hardly noticed. It was snowing cherry blossoms. They streaked everywhere, tumbling off branches and dancing in the air. In the distance, their two children were running in circles trying to catch the falling flowers. The sight was ethereal and beautiful. It filled his heart with joy and it brought to mind his mother's final letter to him.

|

|

Dear Shinobu,

Last night I had a peculiar dream. It was a memory of when I was a young girl. My sisters and parents were sitting together beneath the cherry blossoms all afternoon and into the evening. When night fell my mother lit paper lanterns and the cherry blossoms appeared to glow against the backdrop of night. Drinking rice wine, my father gazed at the drifting blossoms. He used to always recite an old poem, but I had forgotten the words until I heard it in my dream. "Flowers beckoned by the storm fill the garden with white; not snow that scatters but the years of my life."

The poem was written by a court official named Saionji Kintsune in the 12th century. It's strange how the words come back to me now, when my hands are wrinkled and my days numbered. How fleeting life truly is. It took passing my father in age to finally understand what his poem meant. Cherry blossoms are beautiful because they fall – just as life is beautiful because our time is limited. The passage of time stops for no one, so we learn to appreciate and treasure each moment – with family, friends and loved ones. That reminds me, why not do something special this year with your family – take them to the hillsides of Mt. Yoshino where I used to take you as a young boy to view the cherry blossoms. There is a special lacquer box for packing festive meals that my mother, your grandmother, received as a family heirloom. She gave it to me. Now it is my turn to give it to you. It would please me if you took it.

|

|

|

Shinobu placed a hand on the black lacquered boxes his wife had stacked. The sides depicted a pine tree, bamboo shoots and plum blossoms – ‘Three Friends of Winter’ – symbolizing steadfastness, perseverance and resilience. Lingering on the plum blossoms, he mused how art was the only medium that could freeze them in full bloom. The tradition of viewing and admiring cherry blossoms, called hanami, originally began with the viewing of plum flowers and stemmed from a Chinese tradition.

|

|

Emperor Saga, who ruled during the early Heian period (794-1185), was the first to hold a hanami banquet during the cherry blossom season in the Imperial Court of Kyoto. Poems were written praising the exquisiteness of cherry blossoms and how they symbolized the transient beauty of life. Beginning with court nobility and the aristocracy, the hanami tradition eventually spread to the samurai warrior class during the late Muromachi period (1336-1573) and then to all classes of society in the peaceful Edo period (1603-1868).

Hanami, as a major festival celebrating one of the four seasons, came to be associated with tiered food boxes called jubako. Often made of lacquered wood, the tradition of stacking them was not only for functionality but also to symbolize the desire for good fortune to “accumulate.” Records of jubako can be traced back to historical texts from the Muromachi period. They were traditionally made with four tiers to express each season. Although today jubako are most prominently used to serve special New Year’s meals, this was a later development that emerged during the Edo period. Previously, they were used for hanami festivals and called hanami-ju, or for any other outing, for which they were called sage-ju. These were, of course, leisure activities enjoyed only by the upper classes. Consequently, lacquered boxes became items associated wealth and refinement. They were therefore referred to in the honorary tense as o-jubako.

|

|

The respect bestowed on jubako did not stem from their cultural context alone. The art of decorative lacquering elevated them further as objects of admiration and connoisseurship. Lacquering, at its most basic, creates a protective layer over wood that is water and acid resistant. In the East, it was traditionally made from urushiol, the tree sap from a species called toxicodendron vernicifluum, a close cousin of poison ivy. The toxic properties of the liquid, along with its long drying time under carefully controlled conditions made it a craft requiring great skill. Historical excavations in Japan have revealed lacquered artifacts from ancient times, suggesting the ancient indigenous development of the technique. However, lacquering did not come to be recognized as a major art form until after the 6th century when much cultural advancement was introduced from China.

|

|

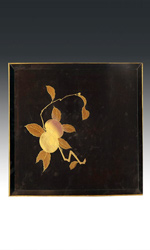

Although heavily influenced by Chinese and Korean aesthetics early on, Japanese lacquer works soon developed a distinct style emphasizing lyrical and elegant surface decorations. Inlays of gold and silver foil enjoyed great favor as did inlays of other materials such as sea shells and minerals. In particular, Maki-e, translated as 'sprinkled paintings,' became praised as one of the highest decorative art forms in Japan. In Maki-e, gold and silver powder was sprinkled over wet lacquer using thin bamboo shoots or fine brushes, a skill that required many years of apprenticeship to master. Lacquer was used to decorate a wide variety of objects, including Buddhist artwork, writing boxes, altars, folding screens, sword scabbards, saddles, furniture and of course, jubako.

Back on the hillside beneath the cherry blossoms, Shinobu told his children about the special heirloom their grandmother had left them. He knew they didn't understand half of what he explained about the cultural and artistic heritage, but he determined he would bring his family to hanami next year and tell them again. It wasn't just the art he wanted them to appreciate, but also what it represented – the ephemeral beauty of life. He hoped everyone could view springtime blooms and scattering cherry blossoms; and they would be reminded to treasure the here and now in all of life's fleeting moments.

|

Download this Article: Art in Bloom – Japanese Jubako and Fubako.pdf