Certified Authentic - The True Nature of Authenticity

PRIMITIVE - Friday, April 07, 2017By Glen Joffe

|

|

"Certified Authentic" is more than a reference to bona fide antiques, meaningful treasures, distinctive collectibles, and art and furnishings from all over the world, the types of items traditionally found at PRIMITIVE. Instead, it is a direct reference to how we define the term authentic and the true nature of authenticity. Historically, our definition of authentic was simple; it meant "used and/or intended for use by the indigenous people." This was especially true many years ago when our focus was exclusively on unique, culturally significant material. In its original context, authentic meant you would find genuine, real objects and furnishings instead of those made purely for export or tourism.

The original definition of authentic included material ranging in age from new to ancient and common as well as rare objects and furnishings. This definition did not automatically translate into higher prices, although people often expressed both joy and disappointment at the price of authentic objects – joy at what they perceived as low prices and disappointment at what they perceived as high. Yet, prices aside, at PRIMITIVE the term authentic translated into objects with a heart, soul and character altogether different than those made strictly for sale.

Yet, what happens to the definition of authentic when you step outside of the realm of cultural objects and furnishings and start dealing with contemporary art, branded furniture, lighting and accessories that are not cultural per se, but nonetheless compelling and frankly, created to be sold? Does the nature of authenticity change? For example, is it fair to say a cultural object like an antique piece of Chinese furniture is more authentic than a contemporary piece of Ralph Lauren furniture? Is an ancient statue from an unknown maker any more authentic than a contemporary statue from one who is known? Stated differently, are there different standards of authenticity for different types of objects?

Answering this question requires a brief examination of some of the issues regularly perceived to affect authenticity, the most common being age, which may be expressed as “new vs. old.” At PRIMITIVE, our guiding principle in dealing with this issue has always been very simple and can be stated as follows: because something is new it is not necessarily bad, and because something is old it is not necessarily good. You could say there is plenty of old junk in the world, and there are plenty of spectacular things made yesterday; and, of course, just the opposite too. Age, even the concept of antique, is a relative term. It should also be added, because something is old it is not necessarily more valuable than something new, and vice versa. In other words, age alone is not a guarantee of authenticity nor does it impart value. It is simply a descriptive term placing an object in a historical context and neutral, regardless of what it implies. In short, authenticity and age are two different things. In this regard, one might consider the new piece of Ralph Lauren furniture as authentic as the antique Chinese piece; and this statement hints at a simpler definition of authentic and the true nature of authenticity.

|

|

If an authentic object can be new or old, what then is left to consider in determining authenticity beyond PRIMITIVE’s original definition? It can be said with certainty that authentic objects tell stories; and this goes for cultural objects, contemporary art and furnishings, and purely decorative objects. These stories are not always evident. They can transcend understanding, and lie beyond the recitation of history; yet, they always relate to why and how something was created. When it comes to why, these stories inevitably address one of a handful of reasons causing objects to come into being; and these reasons are endemic to every culture no matter how far apart they are separated by time and geography. At PRIMITIVE, we call these reasons “common denominators.” They include the pursuit of spiritual beliefs, the desire for security and protection, fertility and abundance, the need to honor the past and foretell the future, the celebration of birth and death, health and wellness, the fulfillment of material needs (politely called mammalian concerns or food, clothing, shelter, transportation, and care of the young), and the pursuit of beauty, meaning and personal expression. Often, these common denominators overlap, but clarity aside, authentic objects and furnishings tell their stories with greater devotion, insistence and truthfulness than their inauthentic counterparts. Yet, a good story is not a guarantee of authenticity.

This leads us to how things are created. The construction, condition, aesthetics, and uniqueness of authentic material are all relevant in establishing authenticity. In the art and furnishings world, copies have existed for centuries; yet, in most cases, how something was created leaves a telltale set of “fingerprints” that can lead a practiced eye to recognize what is authentic or real versus what is not. In today’s day and age sophisticated casting can make a sculpture directly from a mold look almost indistinguishable from a thousand year old original; and digital printing has become capable of emulating even very fine details of paintings on canvas. However, evidence of an identifiable “maker” is commonly revealed upon examination when evaluating how things are created; and this evidence can usually be verified by expert opinion or provenance, which is often combined.

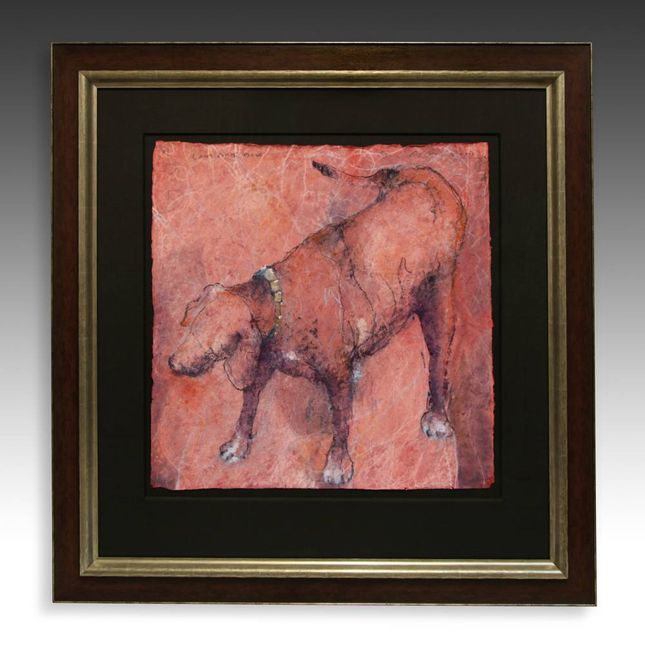

Taken together, why and how have a direct impact on the appreciation of authentic objects. For example, when it comes to cultural objects a “Tiger” rug from Tibet becomes more meaningful when you realize it was a platform for meditation and specifically woven from the finest Himalayan wool using vegetable colors, easily identifiable characteristics for an expert. A Tantric Lingam from India becomes illuminated when you realize it represents the unity of opposite energies and is actually composed of quartz crystal found in only one very specific place on earth. A calligraphy brush from China becomes mysterious when you attempt to visualize the artist who held it or the work of art they created and more real when you see there is still ink in the horsehair bristles, evidence of actual use. Relative to contemporary art, the atmosphere of a Brian Sindler landscape painting becomes more engaging when you consider the effect of his brushstrokes and realize he only uses five colors in his entire palette. An artist’s re-mark from PRIMITIVE Modern can be definitively authenticated by the publisher, PRIMITIVE, and the actual signature and detailing of the artist, Bob Meyer. A contemporary take on the traditional Chesterfield sofa designed by Ralph Lauren shows how classical design is far more adaptable and less rigid than usually supposed, and a dissection of the construction illustrates how carefully chosen, high quality materials and workmanship can help insure longevity, and ultimately, value.

The combined story of why and how is typically recorded by authentic objects in myriad ways; sometimes obvious and at other times obscure. This story inevitably offers both subjective and objective proof of authenticity; and it is conveyed when PRIMITIVE stamps an object as “Certified Authentic.” It is only after certification that factors such as age, rarity, desirability, condition, and the intrinsic value of construction materials can be used to temper

value and determine price. PRIMITIVE's definition of authentic requires an object to embody exactly what it purports to be, and in doing so connect us to the stories of other people, places, and times including now; and ultimately, to our own story too. This is the true nature of authenticity.