Indonesian Buddhas – A Legacy in Stone

PRIMITIVE - Friday, April 28, 2017By Glen Joffe

|

|

The original Buddha, Sakyamuni Gautama, or Gautama Siddhartha, was born in India in the 6th-5th century BCE. Born into a noble family, he left his privileged life to lead the life of a wandering ascetic and thinker. Meditating on the human condition one night while sitting under a Bodi tree, he awoke to find he had realized nirvana, a heavenly state of absolute beatitude and would not be reborn again. He spent the rest of his life as a preacher, his teachings contained in a series of Buddhist documents called the Sutras.

As time passed, Buddhism adapted to new cultures. At the beginning of the first century AD Buddhist doctrine underwent a change from a simple philosophy of life into a set of religious doctrines with Buddha transformed into a deity on the same level as Hindu gods. However, it is thought Buddha never projected himself as a divine entity or master, demanding from his follower’s only personal attainment through meditation and reflection; the object being to liberate oneself from the endless cycle of birth and rebirth to reach nirvana.

|

|

Buddhist missionaries brought their doctrines very early to other countries. Ultimately, the effigies representing the Buddha assumed a local character, and the faces of the deities became influenced by the aesthetic canons of the regions as well as local ethnic types. By the 7th century AD a large Buddhist state called Srivijaya emerged on the island of Sumatra in present day Indonesia. Although technically a city-state, we call it here the Srivijaya “Empire” because its influences were felt far beyond its geographic boundaries, primarily because of its maritime dominance and widespread trading relationships. Yet, trade is a two-way street, so Srivijaya was also influenced by those with whom it traded. It is believed Buddhism came to Srivijaya via trade with India and to a lesser extent, China. However, regardless of how Buddhism arrived, Srivijaya ultimately became an important center for the expansion of Buddhism throughout the region; and in turn, an important center for the dissemination of Buddhist art.

|

|

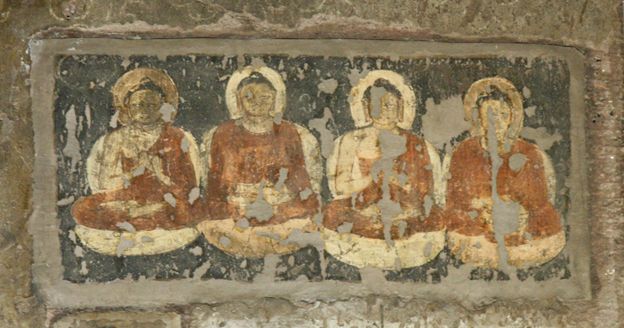

Srivijaya lasted as a cohesive state until the 13th century and was largely forgotten until the early twentieth century when its existence was postulated by a French historian. Since then, it has been shown that Srivijaya was a complex and prosperous society producing refined art directly related to the Buddhist faith of the people. Buddhist art of Srivijaya was heavily influenced by the Indian art of the Gupta Empire (320-550 AD), which was considered a classic “moment” for all types of Indian art including Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist art. Surviving artwork from the Gupta Empire is almost all religious sculpture with a smattering of painting. When it comes to Buddhist art, it can be found at exceedingly compelling and ambitious architectural sites such as the Ajanta caves in the Aurangabad district in Maharasthra state in India. The sculpture and painting found there, while rendered in the Guptan Style, may be traced back to Amaravati art, depending how far back you wish to go. Amaravati flourished in India from the 2nd century BCE to the 3rd century AD.

|

|

The Guptan style may be described as a form of “Greco-Buddhist” art, a combination of classical Greek figural depictions and Buddhist art as it was developing elsewhere. Greco-Buddhist art developed over the roughly 1000 year period between the 4th century BCE and 7th century AD. This art is characterized by strong idealistic portrayals of the human form. If anything can be said about the Buddhist art of Srivijaya and ultimately, Indonesia, it would relate to the simple, naturalistic, refined ideal forms of the Buddhas, which are always depicted with simple, knowing gestures and a serene demeanor. While the adornment of the robes and other attributes might sometimes appear complex, the human form itself was - and is - always beautifully and simply shown.

|

|

Despite the dominance of its culture, the Srivijayan Empire did not leave a great plethora of Buddhist art in Sumatra, where they were based. Of those sculptures found on the island, most demonstrate the same elegance seen in those emanating from the island of Java, where a notable group of rulers called the Shailendra Dynasty emerged in the 8th century. The Shailendra’s were active promoters of Buddhism and covered their territory with notable Buddhist monuments. The the existence of the Shailendra Dynasty and Srivijaya partially overlapped during a period when Shailendra rulers dominated the Srivijayan Empire from their base in Java rather than Sumatra. Certainly, the style of art created at the time of the Shailendra Dynasty became associated with iconic representations of Buddha persisting to the present day in Indonesia.

|

|

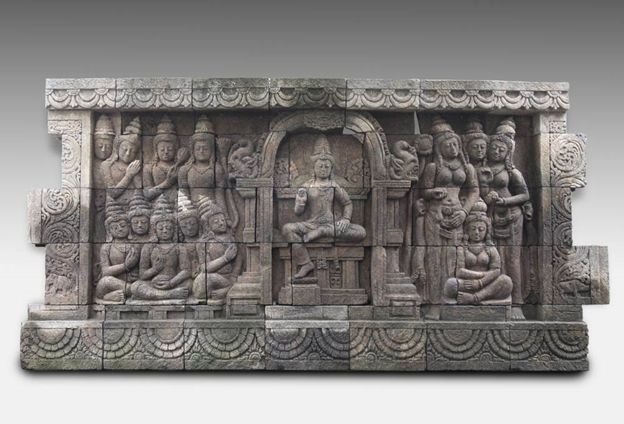

During the Shailendra Dynasty many Buddhist temples and shrines were constructed on their home island of Java. The most famous and magnificent temple is called Borobodur and it is perhaps the largest Buddhist structure in the world. It is estimated to have been built from 775-850 AD. The temple is designed to reflect the Buddhist concept of the universe and is adorned with long series of relief sculptures narrating the Buddhist scriptures. Buddhist art in Indonesia reached its zenith during the Shailendra Dynasty; and nowhere is this more evident than in the sculpture found at Borobodur. This time has been called the golden age of Indonesian Buddhist art, and at PRIMITIVE, many of the stone statues originating in Indonesia are said to be done in the “Borobodur Style” rather than in the style of Shailendra.

|

||

Generally speaking, the characteristics of Indonesian stone Buddhas, especially those in the Borobodur style are uniform. They are almost always composed of lava stone, which may be porous or smooth and dense. They are lifelike with great emphasis placed on correct body proportions. The hair is covered in the design of the 108 snails, which appear as curls, with a pointed ushnisha or top knot. Ear lobes are elongated and brows are beautifully arched. The “third eye” is usually highlighted. The mouth may show a slight smile, but more importantly, the overall expression is one of complete serenity. In fact, at PRIMITIVE it is often said that “Buddha has transcended his role as a Buddhist deity and become an icon for peace and serenity.” This simply means that one need not be Buddhist to have a statue of Buddha in their home or garden. This serenity, the expression of “knowing” and presence, is paramount if virtually all of these statues. Finally, robes may be draped over one or both shoulders, but they are almost always simply depicted in a smooth flowing form. Variations may occur in the hand positions or mudras, and whether or not a Buddha is depicted standing, sitting or reclining. The vast majority of seated Buddhas have their Asana or leg position in the form of Padmasana, the crossed, meditative leg position.

|

|

In Indonesia, the Shailendra’s rule in Java ended in the mid 800s shortly after Borobodur was inaugurated. It took another four centuries for the Srivijaya Empire to disappear due to the expansionism of rival kingdoms. Yet, in all this time, the representations of Buddha barely changed at all. Even as the entire area gave way to Islamic expansion carvers remained resolute in creating images of Buddha that remained faithful to the simple, naturalistic, compelling images developed during the time of the Shailendra rulers. What remains to the present day is an extraordinarily rich artistic legacy found in sculptures now embraced throughout the world as iconic representations of Buddha.