Lost at Sea – Shipwreck Ceramics

PRIMITIVE - Friday, February 26, 2016By Misaki Imagawa

|

|

In the late 1970s a lone fishing boat rocked gently on the waves of the Java Sea just off the coast of Kalimantan, Indonesia. The fishermen appeared as no more than shadows in the grey pre-dawn light. They silently went about their work, hauling in nets full of fish, clams and seaweed. A single deckhand leaned over the boat to pull a net over the side when his fingers curled around an unexpected shape. It was hard, too large to be a shell and too uniform to be a rock. It felt man made. He pulled it onto the deck and crouched down to untangle it from the net and flopping fish. "Rangga, what did you land?” yelled the Captain. The fisherman tugged the large object loose and as the first rays of the sun broke over the horizon, he began to examine it closely. Moments later he shrugged and replied, "Just an old pot."

|

|

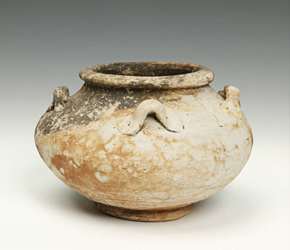

Several hours later the sun was already hot even though morning was not yet over. The boat returned to its dock at Kendawagan and the men began to unload their catch. When the boat was empty and secure, Rangga picked up the pot and headed into the bustling harbor town. No one on the boat really cared if he kept it or not, but he found the vessel pleasing. It had an oval shape, a smooth rimmed mouth, and was dark brown in color with a streak of grey accenting its middle. He was going to give it to his wife as a gift.

On his way home, Rangga stopped at a warung, an open air food stall to grab his favorite snack, sticky sambal rice balls. Eating his food on a rough hewn table, he noticed two European men frequently glancing his way. After a while, the two approached and asked about the pot. Much to Rangga’s surprise they offered to buy it on the spot. Utterly perplexed, he asked what was so important about the old weathered pot. "Although it's just an old Chinese vase,” said one of the men, “it’s intact.”

|

|

“How old?” asked Rangga.

“Several hundred years,” came the reply. “It was likely part of the cargo on a trading ship that sank off the coast."

Rangga decided to take the money and, in turn, he bought his wife a small amulet featuring her favorite god. When he gave it to her, they both agreed that the god had smiled upon them that day.

When this happened, similar incidents were occurring all along the Indonesian and Southeast Asian coasts. Curators and archaeologists were racing each other to find ancient wreckage sites on the bottom of the sea. What surfaced gave precious clues to life in the past. Rangga and other fishermen making similar finds did not know the stories told by these recovered ceramics reached back beyond a thousand years to a time when over half the known world was dominated by Chinese trade.

|

|

While the Silk Road had provided overland trade routes since ancient times, it was overtaken by a dramatic increase of maritime trade during the Song and Yuan dynasties, from the 10th to 14th centuries. At that time, Quanzhou in Fujian Province was considered the largest port in the world. The government actively encouraged and supported foreign trade. Merchant ships would set sail east to Japan, south to the Java sea, all around India, the Middle East, Africa and as far west as the Mediterranean. They carried and traded all sorts of commodities including spices, textiles and artwork. Many ships departing from China or returning from Southeast Asia carried ceramics. Some were lavishly decorative, made of delicate blue and white porcelain while others were earthenware based on ancient forms. Even so, most ceramics were purely practical. For example, many were vessels containing wine, making them the equivalent of today’s wine bottles. Most people, when they think of sunken treasure think of gold bullion, gem studded jewelry and the occasional cannon ball, but these every day, practical objects say as much about where they came from as their more glamorous counterparts.

Despite the overall success and efficiency of maritime trading, the seas could still prove treacherous. Countless ships were lost at sea. Although most trade cargo was destroyed, swept away or disintegrated with time, ceramics fired and glazed at high temperatures were capable of remaining unaffected for centuries underwater. This proved especially true for pieces buried beneath silt. It was purely by chance that hundreds of years later, fishermen began catching these ceramics in their nets, many still intact and looking no worse for wear. Notable discovered wreckages such as the Turiang shipwreck (c. 1370), the Royal Nanhai (c. 1460) and the Nanking cargo (c. 1750) gave birth to a new form of sought-after collectible: shipwreck ceramics.

|

|

In some cases archaeologists have been able to identify shipwreck ceramics, linking them to specific eras, styles and places of origin. However, in many cases pieces remain complete mysteries. The collection of shipwreck ceramics at PRIMITIVE offers a glimpse into different cultures and time periods. Funnel-shaped earthenware from the late Song or early Yuan periods were believed to have carried mercury, an element that had fascinated the Chinese since ancient times. For centuries, alchemists believed mercury was associated with immortality. Physicians prescribed mercury treatment as a cure for a variety of different illnesses. The Chinese were not the only ones intrigued by this liquid metal and its export continued for centuries throughout Asia. The containers for this liquid and other types of liquid were handmade and are distinctly one-of-a-kind. At one time, they were glazed, but after centuries underwater, constantly being abraded by sediment and currents, the glaze has worn off.

While it may be difficult to determine the origin or makers of many vessels in PRIMITIVE’s collection, the mystery underlying each piece contributes to the allure of these sunken treasures. Their appeal is less influenced by where they were made as opposed to how they were preserved – underwater in the depths of the deep blue sea – perhaps the least explored of all the places on Earth. Who knows what the next unassuming fisherman might find? Until then, the ocean will keep its secrets.

|

Download this Article: Lost At Sea - Shipwreck Ceramics.pdf