Molten Magic – A Brief History of Glass

PRIMITIVE - Friday, November 11, 2016Edited by Glen Joffe

|

|

In the year 14 BCE a young Phoenician named Pelles celebrated his 19th birthday just like he spent most days – working in his father’s glass studio on the outskirts of Sidon. Yet, something was amiss. He failed to notice the loud arguing voices in the distance, until he was grabbed from behind and dragged outside. His father was shouting at a tall man clothed in fine robes who was accompanied by Roman guards wearing full armor. The robed man forced a hefty bag into his father’s hands and Pelles recognized the clinking of coins. Wide-eyed, he struggled against the hands holding him, but he was easily overcome and thrown into a carriage. The door slammed shut and within seconds they were speeding off, to where he did not know.

|

|

Pelles hurled himself against the carriage walls for hours, but to no avail. Finally, as night fell, the doors opened and the robed man stepped inside. "Your skills are needed in the capital," he said in a clipped tone. "It is a great honor. Rest assured, your family has been paid in gold and will live in luxury for the rest of their lives. Now stop acting like a wild animal. You are a glassmaker of Sidon and the best there is; or so we have heard." Pelles was skeptical toward the robed man, but for the sake of his family accepted his fate. It turned out his fate was not as bad as he thought. Upon reaching Rome he was given a spacious house with two servants and was treated like an honored guest.

|

|

|

Pelles soon learned he was not the only artisan who had been forcibly 'invited' to establish a glass making industry in the capital. On the outskirts of the city, a large workshop had been built with numerous furnaces. The glassmakers came from all corners of the Empire and beyond. Each possessed a unique new skill that fascinated Pelles. When it came time for him to demonstrate his knowledge, he asked for a hollowed iron pipe and to the amazement of all those watching, blew air into molten glass and shaped it into a perfect vessel. Unbeknownst to him, this demonstration would revolutionize the glass making industry for the next two thousand years.

|

|

Before glass blowing was discovered, glass vessels were made tediously with the lost-wax technique resulting in heavy products that were expensive and time-consuming to make. The innovation of blowing glass shifted glassware from being prized commodities for only the wealthiest to being widespread wares readily available to most social classes. The smooth nonporous surface, translucency and odorless characteristics of glass made it popular for drinking and dining as well as for carrying medicines, cosmetics and perfume.

|

|

Within the span of less than a century, glass making became a distinguished profession. As the power of the Roman Empire spread, new workshops were set up in many regions and “best practices” were shared. Though molded glass-wares continued to be made, the majority were blown into shapes of all designs and sizes. As the Roman philosopher Seneca wrote in his collection of letters known as Epistulae Morales, a glass maker could, "by his breath alone fashion glass into numerous shapes which could scarcely be accomplished by the most skilled hand."

|

|

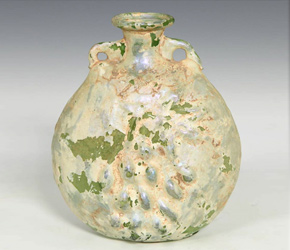

Buried for centuries underground, many ancient vessels have been found intact. In fact, in many instances they have been enhanced by time and nature: the decomposition of glass and the properties of soil have created a dazzling patina of iridescence and marbled encrustation that give these objects a character befitting their age.

Roman glass making never reached the mass production levels as found in pottery and coins, although it did increase later on. By the time the 5th century rolled around, years of war, political turmoil and natural disasters had resulted in the sharp decline of the Roman Empire, and in turn, glass production. Yet, the subsequent rise of the Arab world and the Islamic Empire kept alive much of the glass making achievements that the Romans had manifest: mosaic glass, free and mold blown wares, as well as cut and cast vessels. They would even go on to make their own innovations in areas such as relief cutting and decorating with gilt and enamel. In fact, Islamic glass making was the world's leader in design and technology until the Venetians overtook them in the 15th century.

|

|

However, the Venetians were not without competition. From the 14th – 18th centuries, Bohemia, now part of the Czech Republic, became a renowned center for glass manufacturing. Ultimately, the quality and craftsmanship of Bohemian glass rose to such an extent that it soon became as prestigious and valuable as natural gemstones. Nobles and aristocrats all over Europe coveted the beautiful glassware, especially crystal chandeliers, which could be found in the royal palaces of kings and emperors. In contrast to the Venetian style, Bohemian decorations included bold painted designs upon the glass and intricate blowing techniques resulting in highly refined designs. However, perhaps their most famous innovation was cold-worked glass cutting. This technique utilized copper and bronze wheels to cut and engrave the glass, much like cutting and engraving gemstones.

Throughout history, the advanced skills and available technologies found in glass making centers were often kept highly guarded and secret. Were they worth abducting and holding artisans hostage? Phoenician glass workers were forbidden from traveling during the first century, and it is said Venetian craftsmen were at times confined to the island of Murano under the threat of death. Would glass be the industry it is today if not for artisans like Pelles? For over two thousand years, glass artisans have continued to create incredible artworks – by literally blowing life into them.

|