Printing In Progress... – History of Woodblock Printing

PRIMITIVE - Friday, May 08, 2015 |

|

By Misaki Imagawa

Have you ever printed a picture that looked marvelous on the computer screen, only to pick it up from the printer and experience an utter ‘what the heck!?’ moment? Delicate hues turned into globs of ugly, dark color, conjuring a catastrophic oil spill inside the printer! Or, have you ever printed on different kinds of paper only to discover that some absorbed too much ink while others hardly held the ink at all? Last week, the creative department at PRIMITIVE was filled with the constant whirr of printers in preparation for a PRIMITIVE MODERN project – the introduction of hand worked limited edition prints. These past few weeks focused on a recent series of original pastel drawings by artist Bob Meyer. The sheer number of tests printed to calibrate minute details in each drawing – change, adjust, and readjust; and the dedication of the artist along with our technical staff – got me thinking about the long history of printing and how it ultimately became an art form.

|

|

Before printing was ever considered art, it was very much a practical tool. One of the earliest examples of printing is the use of stamps from Mesopotamia, some dated to 3000 BCE. These were not at all reminiscent of the ink postage stamps we know today; these were incised and cylindrical, and rolled in soft materials like clay to leave decorative imprints. Later, seals of all kinds continued to be used to impress wax. Historians are not exactly certain when ink stamps were first introduced; however, the discovery of a woodblock printed piece of silk in China dating back almost two thousand years suggests that textile printing preceded paper printing. Yet, were the Chinese first to practice cloth printing?

India also has a rich history of textile production that was greatly admired by neighboring countries. As early as 327 BCE, Alexander the Great was said to have praised the “beautiful printed cottons” from India. Records also indicate that Indian textiles were imported into China via the silk routes, which existed for thousands of years. Many of these textiles were printed or “stamped” from highly intricate, hand carved wooden blocks that could produce very fine and pleasing lines. Two thousand years later the tradition of hand stamping textiles still lives on, attesting to the ultimate beauty of these works of art.

|

|

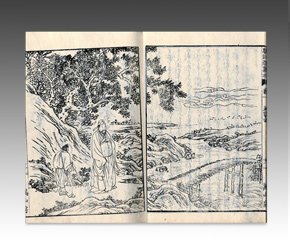

In China, it was Buddhism that prompted writing or script to be carved into woodblocks. Great importance was placed on copying and preserving Buddhist scriptures. The earliest known printed text is named the Diamond Sutra, dating back to 868 AD. Printed on paper, it survived because it was hidden for centuries in a sealed up cave in Dunhuang, northwest China. Though movable type became available later in history, the extensive Chinese character system proved that woodblock printing, even with its necessity to carve the characters backwards, was the most efficient method of creating multiple copies of writings.

In Japan, woodblock printing was also limited to religious writing until the late 16th century. During the following two and a half centuries of the Edo period, the country enjoyed an era of peace and stability. At this time the Tokugawa shoguns, or military rulers, advocated education and encouraged the reproduction and distribution of written texts, which was achieved through woodblock printing.

|

|

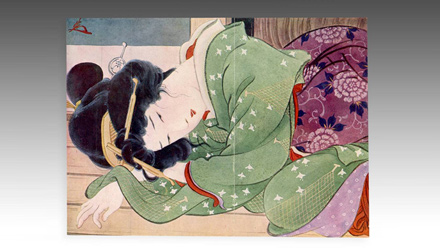

However, in the art world woodblock printing is most closely associated with Japanese woodblocks, undoubtedly one of the highest art forms produced in old Japan. Known as ukiyo-e, and translated as pictures of the floating world, these prints depicted beautiful women, famous kabuki actors, sumo wrestlers, scenes from folk tales and historical stories, landscapes, flowers and erotica. Ukiyo-e flourished from the early 17th century through the 19th century. When the Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu moved his military government to Edo (Tokyo) in 1603, the once small town grew exponentially into a sprawling city. The people who profited the most from this economic boom were the merchants, who occupied the lowest social rank even though they had accumulated wealth of enormous proportions. Ukiyo-e was targeted to the merchants, who were uninhibited in the use of their newfound wealth. This class of people lived a hedonistic lifestyle indulging in theatre and sumo entertainments, visiting the red light district, and buying Ukiyo-e artworks. In a 1661 novel entitled Tales of the Floating World, Asai Ryoi writes:

“Living only for the moment, savoring the moon, the snow, the cherry blossoms, and the maple leaves, singing songs, drinking sake, and diverting oneself just in floating, unconcerned by the prospect of imminent poverty, buoyant and carefree, like a gourd carried along with the river current: this is what we call ukiyo.”

|

|

Asai Ryoi was a famous writer of his time who encouraged and praised this decadent lifestyle. He was also a Buddhist monk, which may appear ironic.

Initially, Ukiyo-e prints were monochromatic, derived from one single carved block. The addition of color came slowly. At first, colors were painted on the prints; but by the mid-1700s artists began using multiple woodblocks, each block related to a different color. By the 1760s full color production was standard and could involve ten or more blocks.

|

|

||

Color printing required exact registration, or alignment of the blocks. In the end, the creation of Ukiyo-e was a collaborative effort involving the artist, carver, printer and publisher. The popularity of Ukiyo-e waned after the Meiji Restoration in 1868. The printing method was increasingly seen as old-school, tedious and time consuming, especially in the face of new Western technologies and the introduction of photography. However, several masters remained loyal to the tradition, and made some of the genre’s most famous artworks. These included artists such as Yoshitoshi, best known for his ‘One Hundred Aspects of the Moon’ series, each print featuring a character and story about the moon; and Chikanobu, who also created many paintings depicting the transition in Japan from a traditional samurai to a modern western society.

In the West, woodblock printing existed, but was not as prevalent as in the East. Instead, lithography, a method of printing from stone became popular in the 19th century. This eventually led to the innovation of offset lithography, an advanced form of mechanical printing still used today to print newspapers and magazines. When eastern prints began to emerge on the western market they impressed and influenced artists such as Gauguin, Monet, Munch, and van Gogh. This influence illustrated the acceptance of prints as fine art. Though technology has made it marginally easier to create prints today, those of high artistic quality still require hours to create and loads of technical skill; and at least at PRIMITIVE, just like in the old days of Japanese woodblock printing, the personal involvement of the artist in creating, tweaking, and touching each limited edition artwork. In looking back all the way to today, one thing has never changed: one mistake and it can still come out looking like an oil spill.

|

Download this Article: Printing in Progress.pdf