Ancient Animals – Symbolism of Chinese Mythological Creatures

PRIMITIVE - Friday, November 18, 2016Edited by Glen Joffe

|

|

A great joy to be found in the researching and collecting of Chinese art is the sheer depth of history and symbolism found in the subject. Chinese art has evolved from over 10,000 years of continuous cultural development and over 3,500 years of written records. The visual language itself is so rich, even seemingly mundane artworks incorporating the written language can become steeped in symbolic significance. Add in the continual repetition and reproduction of ancient forms and motifs and you have both researchers – and collectors – delight. Although the origins of many designs have been lost in time, scholars over the centuries have never stopped researching and speculating on their cultural relevance. Although the symbolism found in Chinese art spans many categories including animals, plants and religious motifs, some of the oldest, most intriguing and widely used symbols were inspired by ancient mythological tales and the creatures associated with them.

|

|

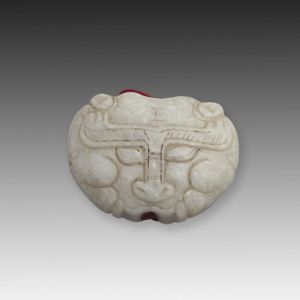

One of the biggest mysteries in Chinese art is the taotie symbol. Typically described as a mysterious monster, its ferocious visage with prominent, piercing eyes and no lower jaw has been found on numerous Shang dynasty (1558-1046 BCE) ritual bronze vessels as central and prominent decoration. The term 'taotie' can be traced back to a classic text written around 239 BCE called Lushi Chunqiu. It described the physical characteristics of the taotie design and noted that it was a fearsome creature capable of devouring humans. Later scholars and antiquarians of the Song dynasty (960-1279), basing their assumptions on the Lushi Chunqiu, regarded the taotie as a gluttonous ogre, a description still widely accepted today. On the other hand, an interpretation from the early 20th century by art historian Max Loehr designated the taotie as a wholly aesthetic and artistic development with no symbolic relevance whatsoever.

|

|

Nevertheless, considering the ceremonial functions of the large vessels they adorned and the highly ritualistic culture of the Shang people, recent scholars generally agree the taotie had some sort of religious significance. Perhaps they were stylized forms of animals connected with shamanic rituals or the representation of harmful spirits. It is even possible they were demonic representations of entities capable of fighting harmful spirits. Would you rather have a pussy cat protecting you or a fierce demon? Whatever their function, the taotie became a revered motif that artists throughout Chinese history returned to time and again. With or without concrete evidence of its origin, the striking appearance and pleasing geometry of the design has preserved its aesthetic and historic appeal from antiquity to the present day.

|

|

Of less mystery, but equal prominence are the mythical creatures guarding each quadrant of the Chinese astrological constellation. The Chinese astrological constellation was formulated during the Zhou dynasty (1046-256 BCE) and became widespread during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 AD) as a fusion of science, mythology and Confucian philosophy. This constellation formed the basis for the twelve Chinese astrological signs and was emblematic of a deep folk tradition involving itself with rich lore to provide a colorful picture of ancient Chinese values, traditions and moral lessons. An essential part of the Chinese astrological constellation was mythological creatures; specifically, the Four Guardians, also known as the Four Symbols, who guarded or were the protectors of the four quadrants of the constellation, each quadrant incorporating three of the twelve signs. Each of the four symbols corresponded to a cardinal direction, season, and element. The Four Symbols are:

1) The Black Tortoise; overseeing the North quadrant, the Black Tortoise is associated with winter and water. Also known as the Black Warrior, the Tortoise is frequently depicted with a serpent because both were believed to symbolize wisdom and longevity in ancient times.

2) The Azure Dragon; overseeing the East quadrant, the Azure Dragon is associated with spring and the element of wood. The benevolent, yet mighty Azure dragon was long considered the greatest of all living creatures with protective powers and auspicious connotations.

3) The Vermilion Bird; overseeing the South quadrant, the Vermilion Bird is associated with summer and fire. Due to its color and corresponding element, the Vermilion Bird is often confused with the fenghuang, the phoenix, which was closely connected to the Imperial Empress. The Vermilion Bird was particularly revered as embodying the virtue of knowledge.

4) The White Tiger; overseeing the West quadrant, the White Tiger is associated with autumn and the element of metal. Regarded as a fierce god of war, legend said a tiger's fur turned white when it reached 500 years of age.

|

|

Mentioned above and frequently confused with the Vermilion Bird, the fenghuang, or phoenix, was considered the feminine counterpart of the five-clawed dragon representing the emperor's authority. In essence, the phoenix was a female dragon. Also, the fenghuang was considered the ruler of all birds and a composite of different species. Its body symbolized the six celestial bodies of sky, sun, moon, wind, earth and planets while its feathers of five colors – black, white, red, green, and yellow - embodied Confucius's five virtues: benevolence, honesty, knowledge, faithfulness and propriety. A house decorated with the image of the fenghuang was said to demonstrate the integrity of its inhabitants. To this day the phoenix and the dragon together represent grace, high virtue and the balance of yin and yang forces to create harmony.

|

|

Another popular mythological creature of protection is the Foo Dog or Foo Lion known as Shi, which translates simply as “lion” in Chinese. Although lions did not literally exist in China, the imagery of the Foo Lion was brought by Buddhist monks from India and Tibet. There, these creatures served as protective symbols to sacred Buddhist sanctuaries. Initially seen as protectors of the Dharma, or Buddha's teachings, Foo Lions existed in religious artworks. They became adapted as imperial guardians in China sometime around the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 AD). Frequently seen in pairs, they traditionally stood guard at entryways to important buildings and structures. Foo Lions, as mythological creatures were believed to have powerful protective benefits. Unlike western depictions of lions, which were rendered in a lifelike manner, Foo Lions were stylized representations intended to reflect the emotion of the animal and its power.

|

|

Foo Lions were usually depicted in pairs, one male and one female representing the principles of yin and yang. The male would be shown holding his paw atop an embroidered ball, which represented the world and authority over worldly affairs. The female would be shown with a cub under one paw, which represented the capacity to nurture or enhance positive principles and events. However, there are many other depictions of Foo Lions. What they all have in common is their protective benefits. Ultimately, the appearance of Foo Lions extended far beyond statuary standing guard at entrances. They became a staple in Chinese art and to this day appear individually and as elements in paintings, lacquer ware, sculpture, and ceramics. They can be seen as decoration on porcelain, adorning censers and incense burners, as jade toggles, architectural details, and even as carvings on furniture.

|

Somewhat similar in appearance, but with different connotations is the Pixiu. Resembling a winged dragon with horns, the Pixiu is a powerful Feng Shui symbol believed to attract wealth and prosperity through its voracious appetite for gold and silver. The fierce appearance of the Pixiu was even believed to effectively drain the malicious energies of demons and evil spirits, converting them into wealth. Both the Foo lion and Pixiu continue to be honored and cherished symbols in Chinese art, architecture and contemporary interior design.

The list of mythological creatures featured in Chinese art could go on, seemingly for endless pages. There is no lack of fantastical beings; however, they represent far more than mere myths or the subject of folktales. They are sincere and candid reflections of cultures past and the mindset of ancient people. As the French philosopher Lucien Levy-Buhl once said, "The anthrozoomorphic statues, which to us appear to be the product of unbridled fantasy are faithful representations of traditional ideas. I might say, and without uttering a paradox, that such art is above all realistic." In this regard, the creation of imaginary creatures to depict intangible concepts is nothing new. The process of visualizing beliefs, philosophy, and superstition into shape and form was mastered thousands of years ago by ancient cultures. The amazing thing is such symbolism is still very much alive – and real – today.