Through the Eyes of the West – European Engravings of the Orient

PRIMITIVE - Friday, August 05, 2016Edited by Glen Joffe

|

|

Long before Google Earth could take us on virtual trips around the world, before we could search the internet for facts, pictures and videos, before encyclopedias even existed, people could only dream of undiscovered faraway lands. In the west, this curiosity was stoked by travelers and traders telling tall tales of ancient cities and the outlandish customs of their inhabitants. In the collecting world this curiosity manifested itself in the form of curio cabinets containing natural foreign objects, collections of prized porcelain and ceramics, and all manner of collectibles. However, the enthusiasm for collecting things from foreign lands was limited to small circles of wealthy nobles who had the time and money to build collections. This all changed in the early 19th century with the widespread production of etchings and prints, which lead to the popularization of the Orient.

|

|

In 1798, Napoleon invaded Egypt and though the military campaign ultimately ended in failure, his occupation proved to be an influential turning point in art. It created a genre that would eventually become known as Orientalism. European presence encouraged scholars and artists to visit Egypt, North Africa and eventually the Middle East to study and document different cultures, environments and customs. Among the many artists who spent significant amounts of time in these foreign lands were now-famous individuals such as Eugene Delacroix and Jean-Léon Gérôme. Other artists based their paintings on travelogues and scholarly articles written by those who had experienced the Orient first hand. In either case, the artworks emerging throughout parlors and galleries soon sparked a popular fascination.

|

|

|

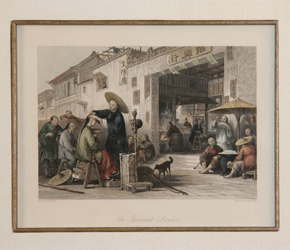

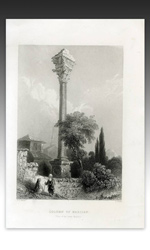

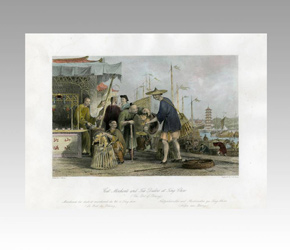

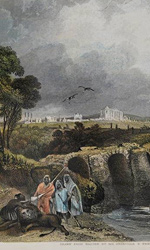

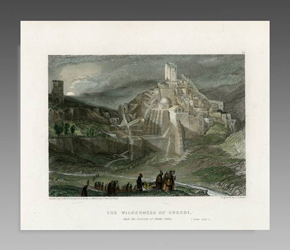

Never before had Europeans seen so many detailed pictures of exotic African and Indian landscapes. From scenes of bustling marketplaces, monsoon waves and ancient ruins to depictions of everyday domestic life, leisure activities and religious customs – it seemed everywhere artists looked there was something remarkable to capture. In particular, landscapes from the Holy Lands in the Middle East drew considerable attention. These became backdrops for religious works. The careful attention to details governing the Orientalist style especially appealed to British Protestants who believed strongly in depicting nature and iconography as faithfully as possible. The accuracy of how the original locations were depicted gave religious works of this period greater authenticity in the eyes of the public.

|

|

However, the limited one-of-a-kind nature of paintings and all original artwork made mass production and distribution impossible. If not for printmaking, enthusiasm for the Orient may have remained in a very narrow circle of artists and their patrons. Instead, publishers, etchers, and artists came together to produce books illustrating topics on travel and religion. In turn, these could be mass produced and distributed on a large, affordable scale to all classes of society.

|

|

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851), better known as J.M.W. Turner, was a Romanticist landscape painter famous already in his time. He received praise from the influential art critic John Ruskin, describing him as an artist who "stirringly and truthfully measures the moods of nature." In 1832, Turner was approached by engraving artists and brothers William and Edward Finden to produce paintings of biblical scenery for a publication. As Turner had never been to the Holy Lands, he relied on sketches and paintings done by artists who had. Within several years he painted a number of works, which in turn were engraved by the Finden brothers and published in the 1836 book Landscape Illustrations of the Bible. Those hand colored prints remain true to Turner's originals, as poetic as any of his oil or watercolor paintings and showcasing the same depth of fascination he held for light.

|

|

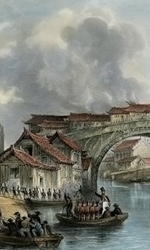

On the other hand, there were artists who did in fact travel to the Middle East. For example, William Henry Bartlett, William Purser and Thomas Allom collaborated between 1836 and 1838 to produce the book Syria, the Holy Land and Asia Minor Illustrated. The book featured 120 of their works illustrating scenes of nature, monuments and religious sites. Later, between 1843 and 1847, Thomas Allom provided illustrations for the books China – The Scenery, Architecture and Social Habits and China Illustrated. Although he never made the trip to China, Allom visited museums, studied sketches by other artists, and familiarized himself with numerous second-hand sources to ultimately produce a significant body of work. His subjects included social customs, religious activities, pastimes, and scenes of nature from the countryside. Allom, an architect and founding member of what became the Royal Institute of British Architects, had an affinity for capturing the significant details found in Chinese buildings. Yet, all his prints, both monochrome and colored, bring to life the curiosity and elegance of 19th century China as it was perceived by the West.

Were European prints of the East accurate historical portrayals of oriental cultures? Not always. They were prone to misinterpretations and stereotypes; however, they reflected a genuine interest in foreign lands on the parts of both the artists and viewers. The works were portrayals of the East as seen through the eyes of the West. Printmaking was the medium through which this fascination spread – the 19th century equivalent of Google Earth. They became an almost obsolete art form as photography became more commonplace. Today those prints, many hand-colored, are still appreciated as memorable, historical artworks capable of taking us on a different kind of virtual trip – one of great aesthetic appeal and antique beauty.

|