Wrapped in Love – Chinese Minority Baby Carriers

PRIMITIVE - Friday, May 27, 2016Edited by Glen Joffe

|

|

In the early parts of the 20th century and far removed from the political and military turmoil shaking the foundations of Imperial China, life in the small outlying villages of the southwest region remained largely unchanged. Isolated by the mountainous terrain, these villages were home to an ethnic minority called the Miao. Night had fallen, but a flicker of light could still be seen in one of the smaller houses; a woman was working diligently by candlelight on a piece of embroidery, her head bent almost to her swollen belly to see the tiny cross stitches forming at her fingertips. Suddenly the door to the house slammed open and a young boy of eight years stomped inside. The woman lowered her work and straightened. "Where were you, Jian?" she asked her son. "I was worried. Your dinner's gone cold."

|

|

Jian made no reply and only glared at the embroidery in his mother's hands before storming through the small living area and into the bedroom. He barely restrained himself from slamming that door too, knowing not to wake his grandmother asleep in the dark room the three of them shared. It hadn't always been this way. Six months ago, when the boy’s father was alive, their house had been filled with laughter and joy – especially when his parents had discovered they were finally going to have another child. But since his father's death, his mother spent all day working in the village and all night silently sewing a carrier for the new baby. Jian's jealousy grew daily, fueled by his grief and loneliness.

|

|

|

"You shouldn't worry your mother so much." His grandmother's soft voice floated in the darkness. A small rustling sound was followed by the gentle flare of a flame, illuminating Hao's wrinkled face and clouded eyes.

"Mother's doesn't care, she spends every night sewing for the baby," Jian replied bitterly.

Hao sighed. "It's about time you learned how wrong you are, child. Open that chest in the corner and bring me the parcel at the bottom; the one wrapped in rice paper."

|

|

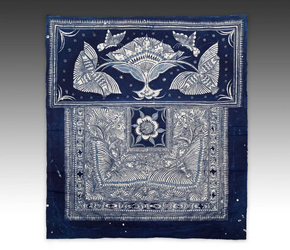

Jian obeyed, wondering what could possibly be so precious to store it in such expensive paper. He watched Hao carefully unwrap it, taking out a beautifully embroidered cloth with immaculate stitches and a captivating design. It was a baby carrier; Jian had seen many in the village as a boy. His father would point out noteworthy works carried by the older girls showing off their skills. Yet none of them, in his opinion, were as awe-inspiring as this one. Two large chrysanthemums bloomed in the center, surrounded by bird motifs and four images of the sun in each corner. The cloth was dyed a deep indigo blue, appearing almost black, and the pale grey silken threads enhanced the grandeur and elegance of the piece. Jian’s eyes widened and his bitterness was overcome with guilt.

|

|

"Your mother was about your age when she began making this for you," Hao said, placing the carrier in Jian's hands. "It took her years to perfect the design. Every minute she was working on it, she was thinking of you. With every stitch she prayed that you would be born healthy, grow strong, and be happy and successful in life. She loved you so much, years before you were even born. Just because you have outgrown the carrier doesn't mean her love has diminished. Thread in the hands of a loving mother," Hao whispered, quoting an old Tang dynasty poem, "turns into clothes on the traveling son."

|

|

The connection between love and embroidery is nowhere stronger than among the minority peoples of China. Miao are believed to be one of the first indigenous inhabitants of China but over the centuries they were driven by the Han Chinese into the southwestern mountains known as the Guizhou province today. Miao is a general term that includes many other sub-branches of ethnicities such as the Hmong, Shui, Yi and Ge Jia groups, famous for their beautiful costumes and in particular, their baby carriers.

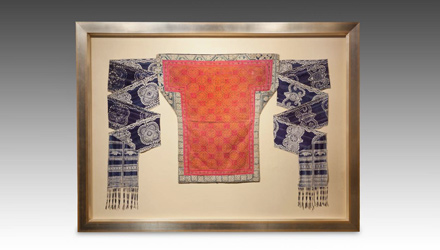

Young Miao girls began learning embroidery around the age of eight or nine and one of the first and most important items they made were baby carriers for their future children. Great thought went into the design and even more effort into its creation. Each and every step, from raising silkworms to producing silk, dyeing the threads, embroidering, brocading and creating patchwork and appliqué was practiced, refined and perfected. Girls dedicated themselves to the craft because weaving and embroidery was seen as a direct reflection of her love, devotion and creativity. As symbols of social status and attractiveness, girls would wear their baby carriers to market, even before marriage, for young suitors to appreciate their talents.

|

|

The designs embroidered on baby carriers held great symbolic value and were expressions of a mother's love, protection and hopes for her child. Popular motifs such as for luck (fu), longevity (shou), happiness (xi) and prosperity (lu) were often used. The butterfly was also an important image unique to the Miao and their creation myth. It is said that god once created a maple tree from which a butterfly was born. This butterfly lay 12 eggs, which gave birth to the creatures of the world, including people. The Mother Butterfly is therefore regarded as the creator of all living things who brings good luck and health to children and blesses Miao women with fertility. The dragon is another motif that differs slightly from the traditional Chinese version. Miao dragons are not figures of imperial authority but rather friends of the everyday people. They are believed to grant happiness and dreams and are also associated with rain, good harvest and prosperity. A common depiction shows two dragons vying for a pearl, one of the Eight Treasures of Chinese tradition, symbolizing the constantly shifting energy and movement of life. Other decorative images include birds, fish, flowers, drums, whorls and meander patterns, all of which have auspicious and protective connotations.

Baby carriers are items of immense value to Miao women who view them as both physical and emotional connections to their children. Once infants outgrow the carriers, they are stored away carefully and sometimes handed down through generations as family heirlooms. Collectors may notice that many baby carriers lack the long strings that were once tied around the mother to secure the baby to her back. When a mother parts with her carrier she often cuts the ties and keeps them for herself for the immense emotional sentiments they embody. Every fiber of the baby carrier is infused with the love of a mother and her hopes for her child. Some say there is no force greater than a mother's love – these baby carriers are testament to that and more – telling us there’s nothing more beautiful than a mother's love!

|

Download this Article: Wrapped in Love – Chinese Minority Baby Carriers.pdf